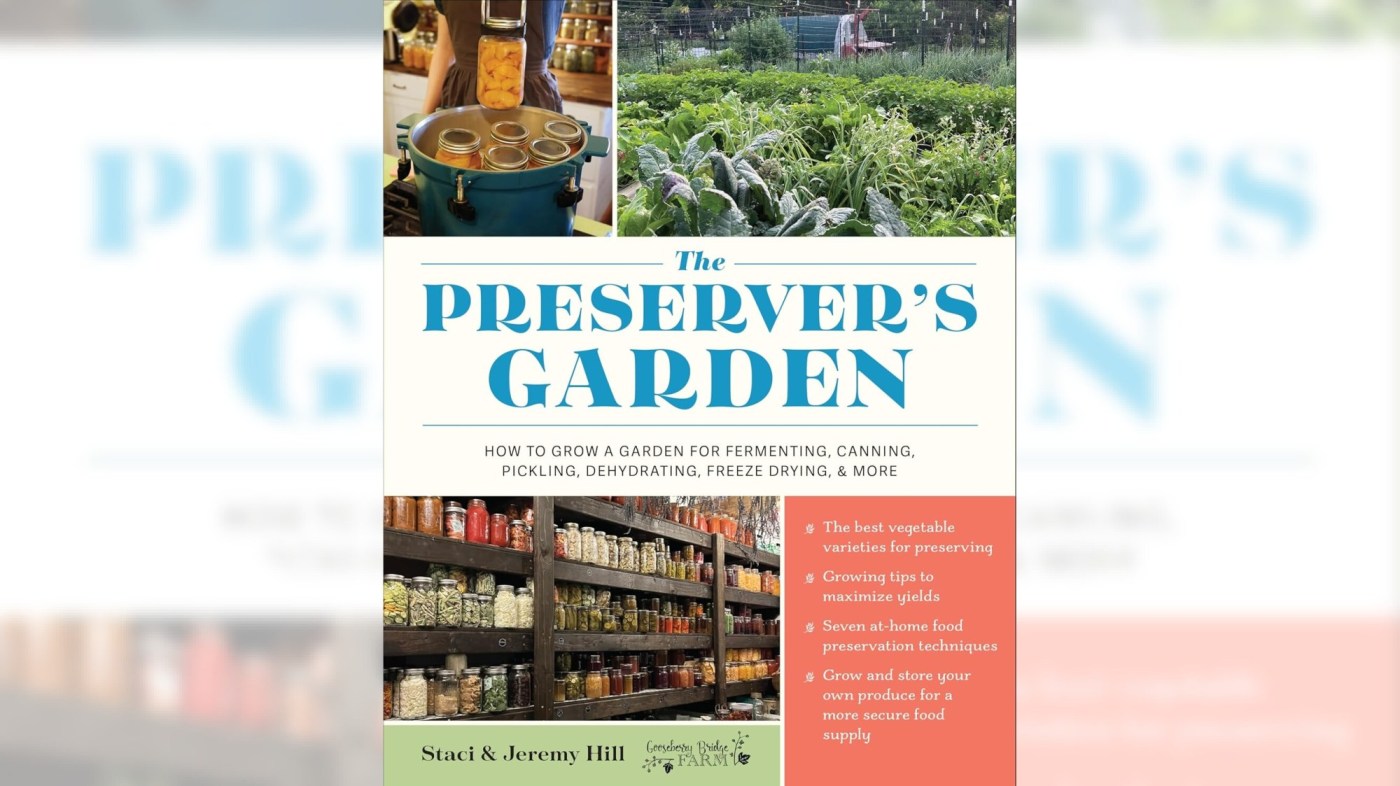

I recently opened a book that fully lives up to the promise of its subtitle: *How to Grow a Garden for Fermenting, Canning, Pickling, Dehydrating, Freeze Drying & More*. Appropriately titled *The Preserver’s Garden* (Cold Springs Press, 2026), this volume, written by Staci and Jeremy Hill, is essential for anyone who has ever had too many apricots or tomatoes to consume and didn’t want them to go to waste. With the processing techniques found here, you will never worry about what to do with an overly abundant harvest again.

Speaking of tomatoes, I learned that there is a whole category of gardeners’ most popular vegetable meant especially for sandwiches. The varieties in question are known as slicer tomatoes. The skins of these varieties come in many colors: they can be black (Black Beauty), purple (Cherokee Purple), yellow (Pineapple, Gold Medal, Kellogg’s Breakfast), or pink (Pink Brandywine, Arkansas Traveler).

The pink varieties are known for their meatiness, with a minimum of seeds and little “interior goo.” Their unique flavor also makes them perfect candidates for soups, sauces, and salsas. Slicers are recommended for those who have never been particularly fond of tomatoes but are open to change.

“If you want to become more of a tomato eater, try an heirloom slicer on a grilled cheese sandwich,” the authors advise, gently spiced with basil salt. “There are few things we crave more, or that bring us more joy than the first grilled-cheese-and-tomato sandwich after a long winter.”

This is a book where you learn something new on every page. For example, I had never heard of basil salt before. The authors share that, “We use basil salt in a shaker on our counter instead of plain salt when cooking or as a table seasoning.”

Basil salt is created by putting a cup of dry, compressed basil leaves into a food processor and blending them into a paste, adding a little water if necessary. Next, kosher salt is added and blended slowly until both green basil and white salt flakes are visible. The paste is then spread on a tray and dried in a dehydrator or on a kitchen counter with a fan. Once dry, it should be stored in an airtight jar.

Freeze drying is highlighted throughout *The Preserver’s Garden*. The authors assert that the day is rapidly approaching when a freeze dryer—whose average home versions vary in size from a large microwave to a hotel-room refrigerator—will be as common as any other kitchen appliance. While its cost is still rather high, growing demand will surely drive prices down.

Produce that is cut up and freeze-dried can last for 25 years, as long as it is kept in a tightly sealed jar with an oxygen absorber (a small packet containing iron powder and salt). Certain flowers, such as zinnias and sunflowers, can also be freeze-dried and utilized as needed for making wreaths and other decorative purposes.

Freeze-dried vegetables and fruits are recognizable by their crisp, crunchy texture. For example, kimchi chips are made from freeze-dried cabbage, and you encounter thin slices or chunks of strawberries, bananas, apples, peaches, mangoes, and pineapples in trail mixes. Freeze-dried foods make excellent snacks on their own and can also be added to yogurt and salads.

If you wish to rehydrate your raw, freeze-dried fruit or vegetable pieces for culinary purposes, simply cover them in cool water in a bowl and soak until soft.

The favored method for preserving herbs presented here is also freeze-drying, because “freeze-dried herbs taste like fresh herbs and are easy to crumble over your food.” Moreover, herbs preserved this way keep their original color and essential oils, maintaining a strong flavor unmatched by traditional air-drying.

***

*The New Natural Food Garden* (Storey Publishing, 2026), by Natalie Bogwalker and Chloe Lieberman, provides all the information you will ever need regarding the design, planting, and care of a vegetable and herb garden.

One interesting feature is the juxtaposition of differing views on certain subjects, proving that gardening is as much an art or a personally customized pastime as it is a science. For example, on the subject of vegetable seedling thinning:

– Natalie thins in two stages:

1. When seedlings have opened their first set of true leaves (after the cotyledons or seed leaves that enclose the embryo have opened), she separates them to one inch apart.

2. After the second or third set of true leaves have developed, she thins to the spacing prescribed for that crop.

– Chloe thins only once, before seedlings grow into each other, sometime between the first and third set of true leaves.

As for growing crops in containers, four soil mixes are suggested: two consist of 60% compost (with a third of this in the form of vermicompost or worm castings), one includes 45% compost, and the other just 33% compost.

When it comes to soil fertility, there are two broad approaches: one focuses on soil mineral content, while the other emphasizes soil life health, including aerobic bacteria and beneficial fungi, especially mycorrhizae. The authors combine both approaches, though I find myself leaning more toward soil health ever since reading about Ruth Stout’s practice.

Stout was a legendary gardener whose only garden input other than water was rotting hay. She grew luscious, pest-free vegetables, building the healthiest soil imaginable that sustained her crops perpetually from one season to the next. To truly appreciate Stout’s work—or anti-work—ethic, read *The No Work Garden*.

A number of tables in this book are invaluable. One that really grabs my attention is “What to do each month in a hot climate (including SoCal) garden.” The gardening tasks for cultivating 30 vegetables are laid out month by month.

For example, among February’s instructions regarding lettuce, “direct sowing (into the ground or a raised bed), transplanting (from seedlings sprouted in pots), fertilizing” are noted. For corn, February’s tasks include “bed preparation, direct sowing,” followed by “succession sowing” in March and April, so you can harvest corn in May, June, July, and August. Muskmelons should be started from seed indoors in February.

***

**California Native of the Week: Antelope Bitterbrush**

*Purshia tridentata* is an anomaly since it is a member of the rose family but has roots that behave like those of a legume. This tough, highly ornamental plant is, for some reason, virtually absent from the nursery trade.

When in bloom, antelope bitterbrush is blanketed with fragrant, bird-attracting yellow flowers against a backdrop of gray leaves on a shrub that can reach six feet tall. It is susceptible to browsing by antelope and deer but is impervious to freezing weather, highly drought-tolerant, yet will accept some water and a little shade.

The plant may lose its leaves in the summer in response to drought, but foliage will return with rain or irrigation.

https://www.sgvtribune.com/2026/01/24/if-your-garden-produces-more-fruit-or-vegetables-than-you-can-eat-try-this/